The Power of Prompting - A Journey from Simple Prompts to Tree of Thought Strategies

- Simple Prompting:

- Chain of Thought Prompting:

- Self-Consistency with Chain of Thought:

- Tree of Thought Prompting:

- Conclusion

- Reference

In the ever-evolving landscape of natural language processing, language models (LMs) have emerged as incredibly versatile tools. These models, such as GPT-4, have demonstrated their prowess in various tasks, from generating coherent text to solving intricate problems. Yet, the key to unlocking their true potential lies in how we prompt them. In this blog, we will embark on a journey through the evolution of prompting strategies, from simple prompts to the cutting-edge Tree of Thought (ToT) techniques, including Breadth-First Search (BFS) and Depth-First Search (DFS) methods.

Simple Prompting:

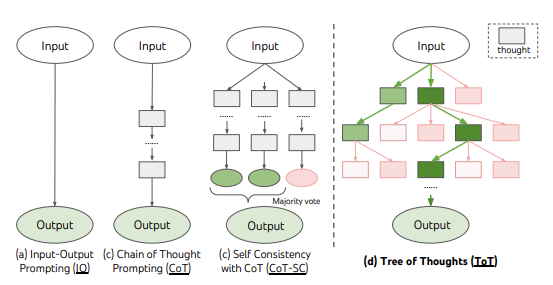

Simple prompting is the foundation upon which we build our interaction with LMs. It involves presenting an LM with an input sequence and receiving an output based on that input. For example, if you wish to know the weather forecast for New York, you might input the question, “What’s the weather like today in New York?” Simple prompting works wonderfully for many straightforward tasks but falls short when faced with more intricate problems that require multiple steps to solve.

Chain of Thought Prompting:

To tackle complex tasks that demand a structured approach, Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting was introduced. CoT bridges the gap between input and output by introducing a sequence of coherent thoughts or intermediary steps. Each thought represents a meaningful step towards solving the problem. For instance, in a mathematical question, CoT might include intermediary equations and logical steps to reach the final answer. CoT prompts are generated sequentially, and the output is determined based on these thoughts. This approach is excellent for problems that necessitate a series of logical steps, guiding the LM through the thought process.

Self-Consistency with Chain of Thought:

While CoT prompting is highly effective, it has its limitations in exploring various thought processes. Self-Consistency with Chain of Prompt (CoT-SC) was devised to address this challenge. This ensemble approach involves sampling multiple chains of thought and selecting the most frequent output. CoT-SC is particularly useful when there are multiple valid ways to solve a problem. By exploring a richer set of thoughts, CoT-SC improves the fidelity of the output. However, it does not delve into different thought steps within each chain.

Tree of Thought Prompting:

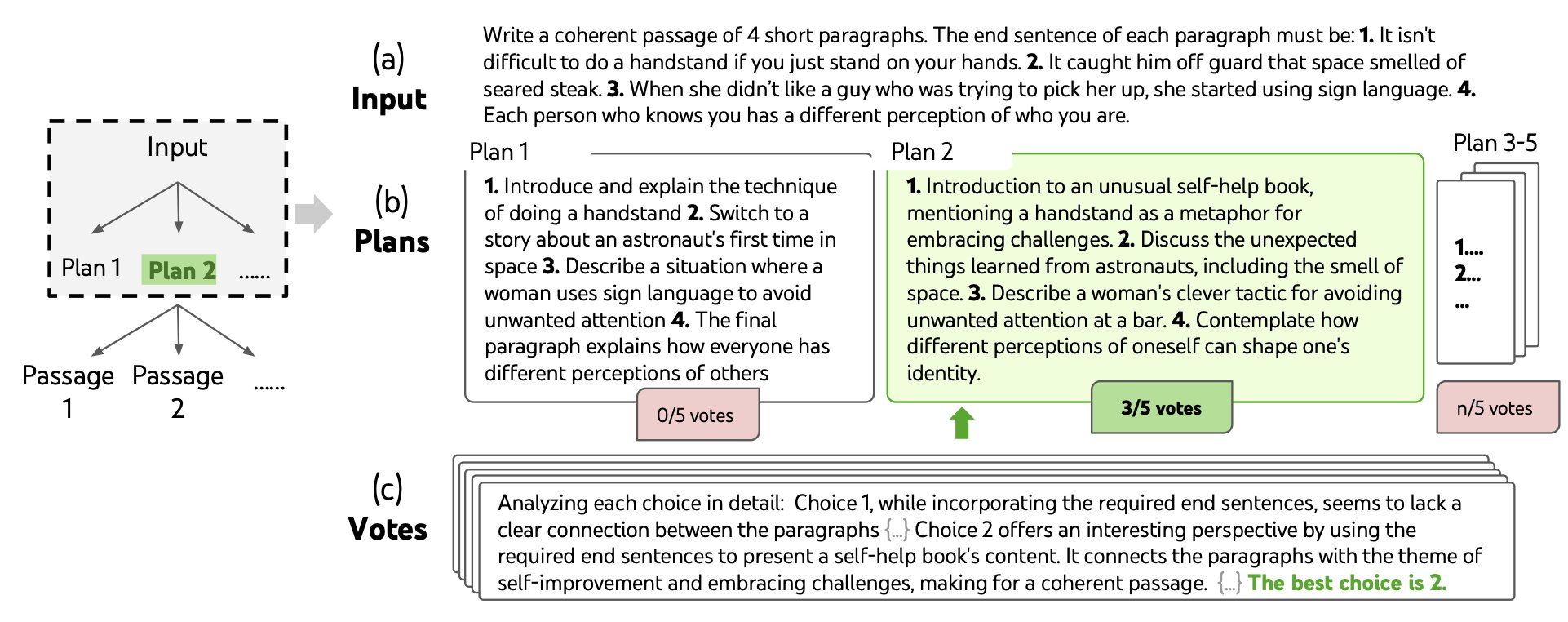

Now, let’s dive into the cutting-edge Tree of Thought (ToT) prompting strategy. ToT takes a quantum leap beyond CoT-SC by introducing a structured tree-like framework to represent the problem-solving process. Instead of a linear chain of thoughts, ToT frames problems as a systematic search over a tree structure. The ToT approach seeks answers to four key questions:

Thought Decomposition:

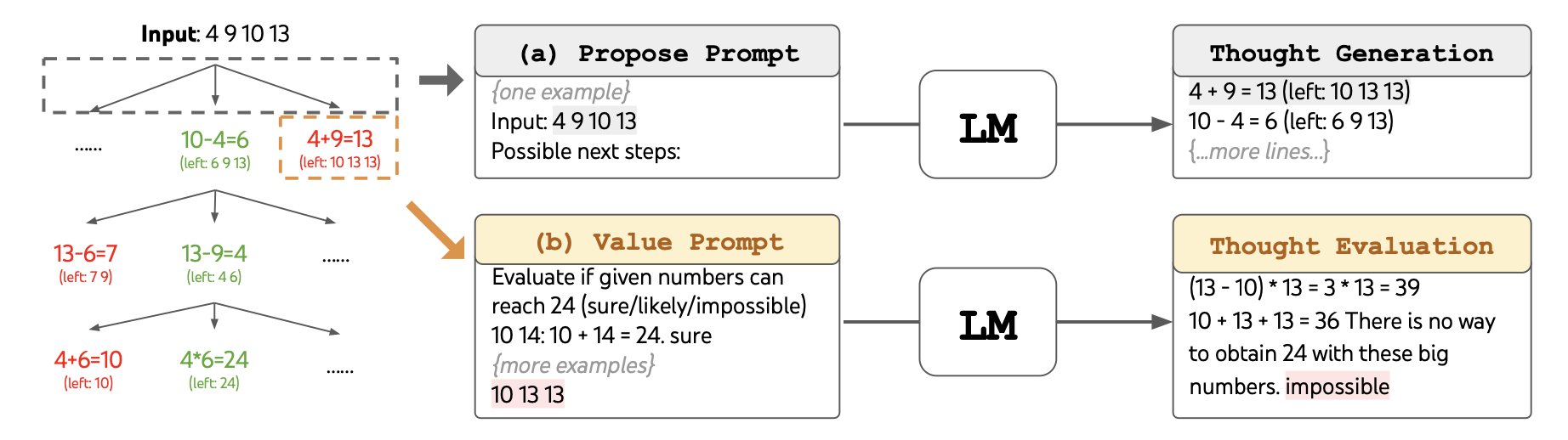

ToT decomposes the problem-solving process into intermediate thought steps. Depending on the problem’s complexity, a thought can range from a few words to a whole paragraph. It should be small enough to allow the LM to generate diverse samples yet substantial enough for evaluation.

Thought Generator:

ToT generates potential thoughts from each state using two distinct strategies. First, it samples independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) thoughts from a CoT prompt, ideal for rich thought spaces where diversity is essential. Second, ToT proposes thoughts sequentially, suitable for more constrained thought spaces. This sequential approach ensures that different thoughts are proposed within the same context, minimizing redundancy.

State Evaluator:

Search Algorithms:

Breadth-First Search (BFS):

Initialization: The BFS algorithm begins with an initial state, often representing the problem’s input, denoted as x.

Expanding States: BFS maintains a set of the b most promising states at each step. These states represent different partial solutions, where each state consists of the input and a sequence of thoughts constructed so far. The algorithm generates new thoughts from these states and evaluates their progress toward solving the problem.

Evaluating States: The state evaluator function V(pθ, S) assesses the progress made by the states in solving the problem. It serves as a heuristic for determining which states to keep exploring and in what order. States are evaluated independently, and the most promising states are selected based on their evaluations.

Exploration: BFS explores the most promising states across the tree, ensuring that states at the same depth level are explored before moving deeper into the tree. This breadth-first exploration allows BFS to consider a wide range of potential solutions simultaneously.

Backtracking: BFS does not backtrack to previous states; it focuses on exploring the breadth of the search tree. It continues expanding and evaluating states until it reaches a specified step limit (T) or exhausts the search space.

Output Selection: Once the exploration is complete, BFS selects the most promising state as the output, and this output is used as the solution to the problem.

Depth-First Search(DFS):

Initialization: Like BFS, DFS starts with an initial state representing the problem’s input.

Expanding States: DFS explores the most promising state first and generates new thoughts from it. It then evaluates the progress of these thoughts in solving the problem.

Evaluating States: The state evaluator function V(pθ, S) assesses the progress made by the states, similar to BFS. However, DFS evaluates states independently and may apply a threshold (vth) to prune less promising branches.

Exploration: DFS explores the search tree in a depth-first manner, focusing on a single branch at a time. It backtracks to the parent state if the current state is deemed impossible to lead to a solution or if the step limit (T) is reached.

Output Selection: DFS continues this exploration until it either reaches the step limit or finds a solution. The final output is determined when a solution is found, or the search is exhausted.

Conclusion

In summary, the way we prompt LMs has evolved significantly, from simple input-output prompts to advanced strategies like Chain of Thought prompting, Self-Consistency with Chain of Thought, and the groundbreaking Tree of Thought prompting with its BFS and DFS methods. These strategies enable LMs to tackle complex problems, opening up new possibilities for natural language understanding and problem-solving. As LMs continue to advance, exploring and refining these prompting techniques will remain a vital area of research and development.

Reference

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.10601.pdf